The 2024 excavation season in The Globe Field, Llantwit Major, will run from 20th May until 14th June. As in 2023, this is a training dig for Cardiff University archaeologists, but we will be welcoming volunteers into the project too. Digging will take place on weekdays only.

Background

The blog for the 2023 season contains a lot of background information on the site and links to various internet resources, so anyone interested should check those.

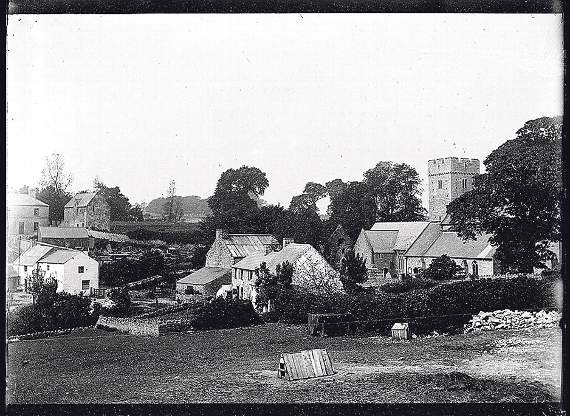

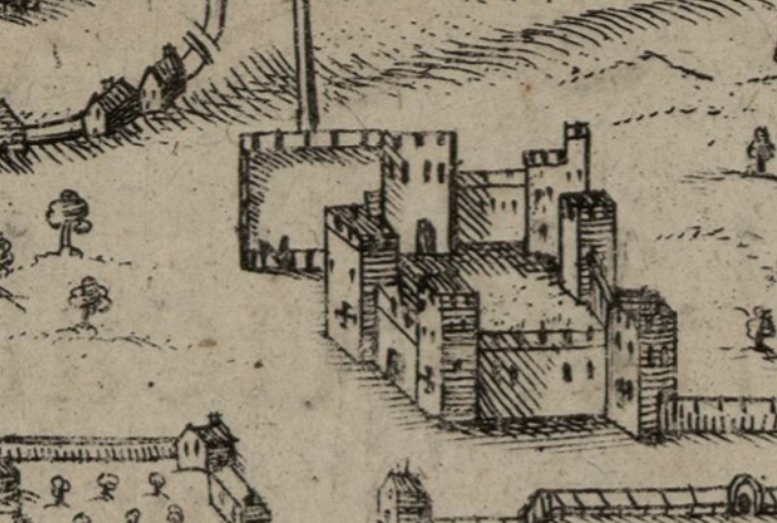

The research goal of the project is to provide some clarity on the nature of the early medieval monastery at Llantwit – and in that endeavour the university is supported by the ‘Dr DG Smith Memorial Fund’. The project started with much geophysical survey and out of that work it was possible to propose a possible extent for the early medieval monastic enclosure.

The excavations in The Globe Field were designed to investigate a series of stone banks or walls, that subdivide this enclosure internally.

Provisional results from the 2023 dig

The results of the 2023 excavations are not yet fully compiled (switching from an August/September dig to a May/June timing meant a rather short winter for the post-excavation studies to be completed!), but a tentative story for the development of the site is emerging (although it might easily be altered by the results of the 2024 season!)..

The earliest activity detected in 2023 was part of what was probably a small gully, containing some metalworking waste and a moderate quantity of charred wheat. This wheat was radiocarbon dated to cal. AD 596 – 664. This date is excitingly early – although significantly later than the time of Illtud (usually interpreted to have lived very approximately AD460 – 525) and Samson (very approximately AD 490-565), it probably predates the visit of Samson’s biographer to Llantwit (probably AD 680×700).

As the fame of Llantwit as the cult centre of Illtud, and probably as a burial ground for the kings of Glywysing, grew so a large area appears to have been given over to burial. West of the stream at the Globe Field there are burials of the mid-7th to late 8th centuries, the 2023 excavation produced an infant burial of the 8th-9th centuries as well as a substantial amount of disarticulated bone eroded from somewhere up slope (including a femur with a similar radiocarbon date to the in-situ infant). Undated burials were found at the Hayes in the 1860s. The late 8th to 9th century is also the period of the inscribed stones now in the Galilee Chapel, suggesting that high status burials were focused on the modern church site.

After the 9th century, the site in The Globe Field appears to have been used for livestock, perhaps pigs, and significant erosion occurred during thee 10th and 11th centuries (including of earlier graves). This occurred at a time when the documentary evidence for Llantwit also breaks down – there are no more written references to an Abbot for instance. The focus of local secular power may have moved eastwards, the forces of Dyfed invaded Glywysing in the mid-10th century and the site may have lost royal patronage.

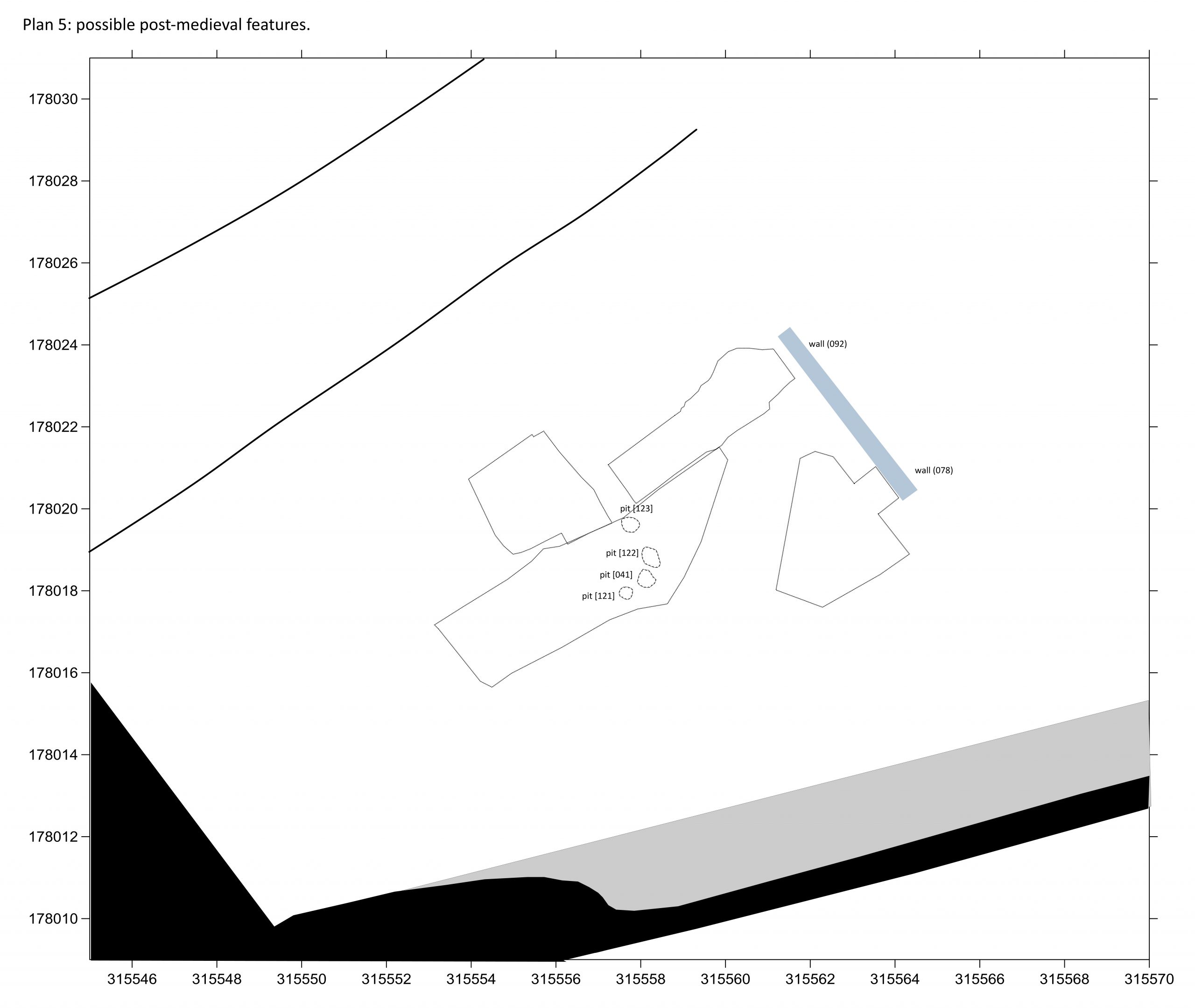

A complete change of land-organisation and land-use was marked by the creation of a network of drystone field walls (the features that had attracted us to the site in the first place). These walls, each 70-80cm thick, bounded a series of small fields and currently appear to date from around the time of the Norman invasion (c. AD 1100). They may reflect major changes brought to site either following the granting of the church to Tewkesbury Abbey or from the influence of the rise of Llandaff Cathedral. The ‘Life’ of St Illtud, written at around this same time, certainly shows a rather pro-Llandaff agenda, as well as a clear intent to stimulate pilgrimage. These fields show the development of lynchets – in which soil moves downslope (usually because of tillage), eroding at the upper edge of the field and accumulating at the bottom of the field, that developed rapidly during the 12th century.

The network of small arable fields does not appear to have survived long. The build up of the lynchets probably caused the stone walls to collapse by the end of the 13th or early in the 14th century.

The later history of The Globe Field appears to have been mainly as a pasture, except for the eventual subdivision of the field to provide a vegetable garden in its southern half.

Blog

26/6/24: what took over 5 weeks to dig out took less than 5 hours to put back in. Thanks to Billy of Clive Edwards Contracts Ltd for a job neatly done! 10 months, 2 weeks…

20/06/24: the final day of fieldwork for this season. Some fresh work was undertaken in the central area – locating the lower limbs associated with one of the skulls in the adult grave, but also locating two ‘new’ infant burials. This probably means we have 12 or 13 infant burials – subject to detailed osteological examination of the disturbed skulls. Bizarrely, excavation of a hollow thought to be possibly one of the ‘missing’ graves, only produced part of a fish!

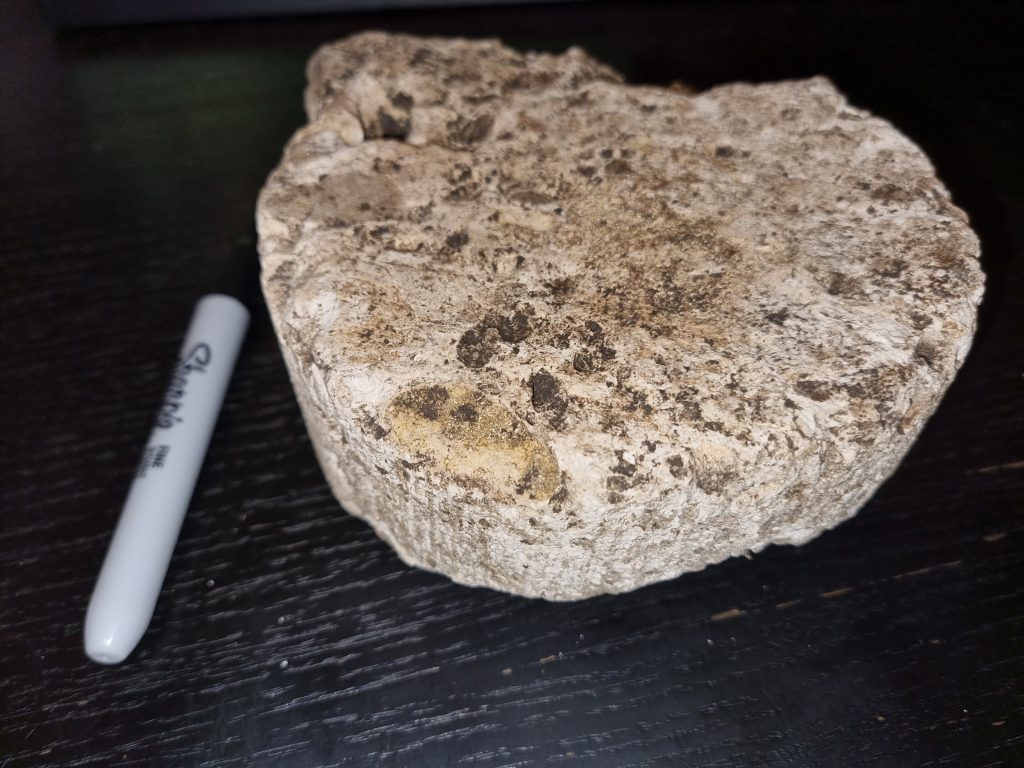

In the SE corner work continued on the ditch or gully below the stone dump. No further convincing evidence was found to determine whether this was a natural or cut feature. It contained much iron slag derived from the adjacent smithy, but also copper slag and a large crucible base.

The site has now been carefully overlain with a geotextile membrane in preparation for its imminent backfilling. The best current estimate is 10 months and three weeks until we will be back on site.

I hope that once the last 5 weeks have sunk-in there will be a summary blog post, but for now it only remains to thank everyone who contributed – 309 days from students (on their course or as volunteers), 112 days from the supervising team and a massive 263 days from the volunteer group. Thank you all for your hard work in this exciting project.

19/06/24: work continued to finish-up in 3 areas today. In the central area a large, irregular stone filled ‘pit’ was found beneath our barrow run. The fill of this pit resembled that of the base of the overlying post-medieval stone drain. Although the pit could have been a deliberate sump, the irregularity suggests it might have been produced through removal of a root ball during construction of the drain.

Also in the central area work continued on try to understand the infant graves cut by the later N-S adult burial. The partial remains of one infant were lifted – skull surviving to one side of the adult grave and lower legs to the other. At least one, and probably two, further graves were similarly cut by the adult grave. Just to the east, a sixth probable grave at the southern end of the eastern row was recognised – bringing the likely total to nine infant/child graves in the group.

In the SE corner of the site, a sondage was dug across the prominent stone backfill deposit. The main stone fill was fairly shallow – coming down onto our only example so far of solid bedrock, but in the corner of the trench there was a deeper feature. It was unclear whether this was part of the ‘palaeochannel’ or a discrete cut ditch/gully feature.

18/06/24: in the central part of the trench worked continued in the area around the large stone blocks. To the west of these, further large stone blocks appeared, set in an large area of disturbed natural, to the north, a distinct linear cut and to the east, two probable graves, the northern containing the pebble surface bounded by small rock slabs.

In the SE of the trench work continued on a section through the late pre-Norman stone fill. No firm conclusions on this area can yet be drawn, but hte stone deposit did produce a riveted bronze object, perhaps a simple buckle plate.

17/06/24: this was the first of a few days we will spend tidying up the site and resolving any features that might be lost when we backfill over a geotextile membrane. Most of the effort today was in the central area , where the contexts into which the graves had been dug were examined, as was the base of medieval cultivation soils just to the west (there appear to be several hollows filled by bone- and stone-rich fills, as well as a narrow linear feature interpreted as a furrow). In the SE of the trench, a feature expected to be a grave was partially excavated – but that interpretation seems likely to need to be revised.

14/06/24: the final day with the full team!

The shelter allowed the delicate work of lifting the NS burial in the central part of the trench. The body was probably shrouded and was placed in a rather irregular grave.

To the west of the site, a linear zone of stones proved not to be a wall, but to be a scatter of stone overlying soils with large pieces of medieval pottery and to correspond to the position of large stones lying on the surface of the disturbed natural clay. This is tentatively interpreted as a long-lived zone for the disposal of stone between narrow NS zones of medieval cultivation.

To the east of the site, another adult burial was examined. This had been placed in a grave of which less that 100mm depth was preserved below the base of the medieval cultivation soils. Since last year, we have known that 8th-9th century burials were eroded by, and redeposited down, the shallow gully in he south of the site. This burial provides graphic evidence for the extent of that early erosion.

The sequence of features in the central part of the site may perhaps show some interesting parallels with the sequence at St Patrick’s Chapel (Whitesands Bay) – the stone setting with white pebbles, surrounded by a cluster of EW infant burials, in turn cut by a NS adult burial. Today’s work has shown that our cluster of features is underlain by a cereal drying kiln – presumably associated with the charred wheat sampled immediately to its NE that gave a date of cal. AD 596-664 last year. It is a very protracted history of significance for this particular spot over 250 years or so.

Thanks are due to all those who have participated over the last four weeks. I haven’t counted the hours but, rounding up to whole days there have been 602 person-days worked on site so far this year – 256 from students, 102 from staff and 244 from volunteers. Thank you to you all. There will be just a few days of finishing up, tidying, dismantling the site and readying the trench for next year, to come next week.

13/06/24: the weather took a turn for the worse today, so continued work on the complex of graves had to be undertaken beneath one of the shelters that had been moved into the trench. The southern infant grave retained a poorly-preserved partial skeleton, which has now been lifted. The adult skeleton has been cleaned as far as practicable in the conditions. Its grave was very shallow in the south and the disposition of the bones suggests the body had been buried in a shroud.

12/06/24: today was dominated by burial archaeology. The southern of the three investigated infant graves proved to contain a partial skeleton, to its west a N-S oriented adult burial truncated other E-W infant graves and an apparently isolated adult burial was located in the SE of the trench. Elsewhere in the trench there was some possible evidence for bronze-working to the west, increasing evidence for the processing of raw iron blooms in the NE and in the central area the N-S grave contained abundant charred wheat, probably derived from the underlying early feature it cut.

11/06/24: this was another very busy day, dominated by attempts to unravel some particularly complicated burial archaeology. One quieter period involved some filming in the Galilee Chapel – it was so nice to see the stones cleared of all modern obstructions and just to be able to take the time to read all the inscriptions.

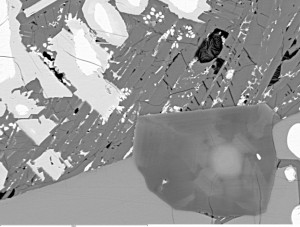

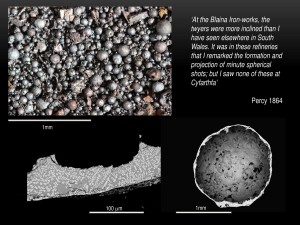

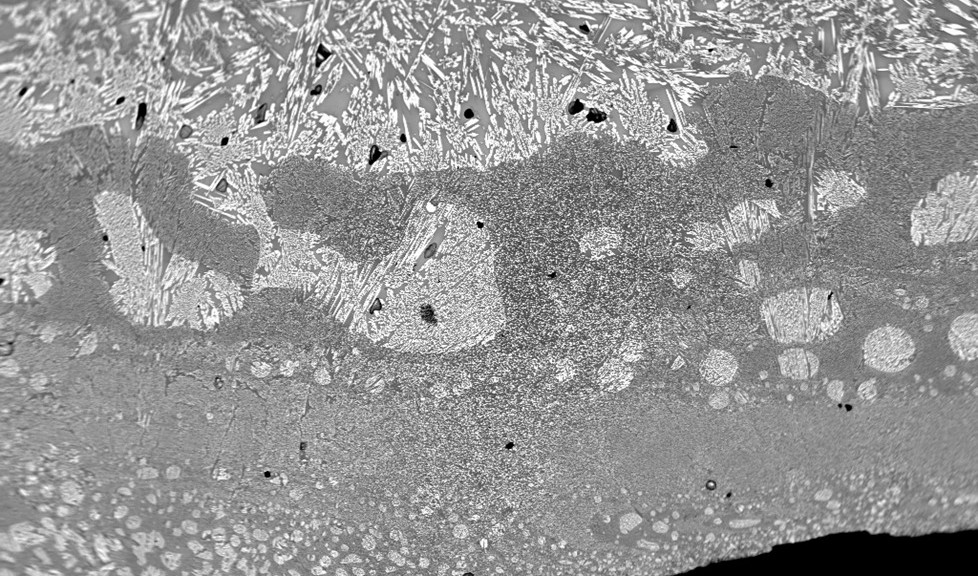

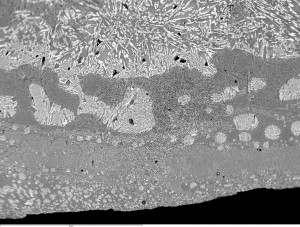

The day also necessitated the rapid digestion of all the dates that arrived yesterday. The first key outcome of the new dates is that the iron-working activity (our Phase 2) appears to be mid- to late 7th century (or just possibly into the 8th). Interestingly the dates on the human remains from 2023 Trench 2 (in the woods, across the stream) were identical to this.

Deposits of phases 3 and 4 (where at least partially sealed by an overlying Phase 5 wall) contained charcoal particles that were clearly derived from the Phase 2 activity, but dates on wheat grains gave ranges spanning the 11th and early 12th century. Away from the walls, Phase 4 deposits showed probably intrusive wheat grains that gave dates spanning the late 12th and early 13th century (the age of the overlying Phase 6a and 6b cultivation soils on the upslope side of the N-S wall on the basis of their pottery).

West (downslope) of the N-S wall, the deposits of the negative lynchet (Phase 6c) gave dates running from the late 13th century to the late 14th century, suggesting that the collapse of the wall is likely to have been well within the 14th century, slightly later that assumed.

Taken together, the dates we now have on human remains across 3 different areas, with 2 dated individuals from each, do not appear to support a simple outward growth of the area of inhumations southwards from the area of the modern church – but the data cannot discriminate between polyfocal activity and a northward spread. This is fascinating and will guide the choice of future investigations.

10/06/24: an extremely busy day on site today, but good progress with the archaeology right across the trench: continued removal of later medieval cultivation in the west, further investigation of the area of infant burials in the centre, exposure of features below the smithing waste in the east and continued excavation of the channel in the south.

Today also saw the receipt of all the delayed radiocarbon dates from last year. A full account of those will follow another day.

09/06/24: just a small group went out to site today, to prepare for our final, busy, week. The removal of the thin remaining layer of medieval cultivation soil in the west-central part of the trench revealed a rather enigmatic arrangement of large stones with a small area surfaced with small rounded pebbles. Understanding this complex area is just one of the tasks for the next few days…

08/06/24: this was a lovely day for the open day – it just seemed to get hotter as it went on. Sharing the day with the ‘These 3 Streams’ festival meant a constant flow of people popping in to see what we’ve been doing. The first visitors arrived around 9.30 and the last of the well over 200 people who came down to the Globe Field left around 5.30. Thanks to those who came came to help – and to the visitors for all being so engaged!

Besides looking after the visitors the team also found time to work on a grave cut that had been hidden by one of the drystone walls in 2023. The wall was removed this week, so the grave could be investigated. It proved to be very small, with only tiny scraps of bone surviving – perhaps suggesting it was the grave of a very young baby. Transverse slabs of rock protecting the head end of the grave were an interesting feature.

07/06/24: early medieval levels were finally reached across most of the central section of the trench, although two sections of the 12th century walls and a probable soakaway remain in the NE corner. The surface is yet to be thoroughly cleaned but (with the eye of faith) the southern margin of the probable grave cut partially exposed last year may be visible. A N-S alignment of large stones just to the west of the old sondage was unexpected and requires further investigation.

The trench is now ready for tomorrow’s open-day…

06/06/24: today’s main task was the removal of the main sections of drystone wall. The rectangular stone-filled pit in the angle between two of the walls was also investigated – and proved to be a shallow pit lined by very large stone slabs and infilled by large limestone blocks overlain by smaller ones. It appears to be some form of soakaway- and the interstices of the fill yielded various large pottery and bone fragments, as well as a fiddle-key nail. The oval stone patch to the NE appears likely to be somewhat similar.

In the west of the site, a N-S line of stones is still proving enigmatic. In the SE, an inclined layer of large stones may be the same as that found beneath the N-S wall in the southern sondage last year.

05/06/24: today’s main task was to complete removal of the medieval cultivation soils, to leave the drystone walls free, ready for removal. This was slightly thwarted by the complicated stone features in the NE which now appear to be medieval underneath the recent rubble investigated yesterday. The structures include a length of drystone wall perpendicular to the main N-S wall, possibly with a right-angled corner at its E end, and an oval patch of heavy stone to its S. The possibility that this represents part of a building cannot currently be excluded.

Steady progress was also made with sieving – with all four sieves going almost continuously. Other tasks included cutting a new access ramp through the 2023 backfill to allow easy access into the deepening trench. Finally the task of preparing the site for a drone photo took involvement from everyone – so the opportunity was taken for a team photo!

04/06/24: another day of rapid progress – involving great efforts from those digging and from those sieving. Natural was reached down almost the whole E margin of the trench. Much of the centre and east is now down to the level of the base of the Norman walls. A complication arose in the NE trench corner, where substantial stone ‘patches’ and a posthole, probably of 19th to 20th century date, took some time to resolve.

The ‘find of the day’ was a small socketed iron arrowhead, just 50mm long and 12mm wide, with slight barbs and a tip that has been folded-over, presumably by impact. The long socket probably allows for this arrowhead to be placed in Jolley Class MP2 (although it is smaller than many examples). Jolley ascribes a wide 11th to 14th century age for this multipurpose (hunting/military) type, quoting local examples including specimens from Llantrithyd.

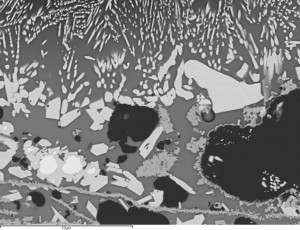

03/06/24: with just five days work before the open-day, the team rose to the challenge of working out the medieval cultivation soils. The E side of the trench showed two distinct stratigraphic successions – brown stony soils in the S and soils with an elevated content of slag in the N. These slaggy soils proved to overlie disturbed natural at a shallower depth than expected (good news!) and showed hollows or cut features with very dark, charcoal- and slag- rich fills. There was evidence for both ferrous and non-ferrous metalworking.

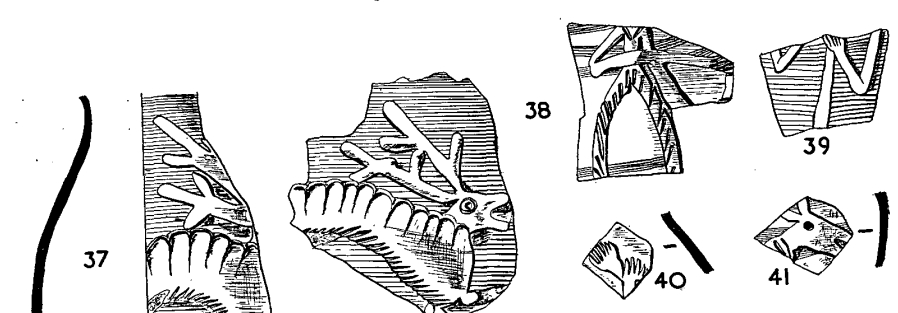

The brown soils further south produced a tiny strap end (Thomas type J2) with a simple circle and dot ornament, thanks to Steve McGrory’s careful detecting of the spoil. These simple types are difficult to date, but could be early medieval.

31/05/24: today marked the half-way point of the fieldwork. Good progress was made in removing medieval deposits, including cultivation soils in the east and north (where the continuation of the N-S wall was exposed) and wall collapse material in the centre (where the main N-S wall was cleared). The cultivation soils in the E produced a good assemblage of 13th century pottery together with a Henry III halfpenny (this tiny object presents some excellent spotting by the students on the sieves!!).

30/05/24: a day of steady progress across the site. In the SE the level is now down to the medieval cultivation soils, in the centre the kerbing of the post-medieval drain has been removed and in the west, exploration of the sequence towards the stream has started. The most notable progress was probably in the centre where the N-S drystone wall has been located within the mass of stone to the south of the old sondage and, in a somewhat irregular form, to the north of the sondage. Very windy conditions today prevented the taking of any new drone images.

29/05/24: the weather was much better today and the site progressed well. The fills of the post-medieval drains are now removed (apart from the ‘kerb’ stones of the western drain). Both of E-W drystone walls appear to lose their character away from the N-S ‘spine’ wall – which is intriguing and needs further investigation.

28/05/24: much of today was quite wet, which restricted the activities undertaken. Nonetheless, good progress was made, with most of the fills of two post-medieval drains removed. Instead of the expected Norman drystone wall, a apparent spread of stone is appearing in the western arm of the trench.

27/05/24: It was a hive of activity on site today. It was the first day we’ve had a proper pot-washers circle and the trench progressed a long way. The northern sondage from 2023 has now been cleaned, with the hearth, grave, gully and other features re-exposed.

24/05/24: The site was very busy today with over 30 people either in the trench or manning the sieves (we now have three large sieves going continuously) as well as what felt like a continuous stream of visitors. In the deep section of the old trench, the smithing hearth has now been exhumed. To the east, the unexpected stone feature appears to be a second later post-medieval drain and, to the west of the trench, the medieval cultivation soils appear to have been reached. The progress in the first week has been excellent and I hope we will be in ‘fresh’ archaeology across the whole trench by the end of Monday. I had intended to illustrate progress at this point with a drone image, but it was just too gusty at the end of the day.

23/05/24: significant progress was made today on clearing the old trench. The bottom was reached over part of the deep section (the 2023 ‘northern sondage’). Removal of the post-medieval soils continued in both the western and eastern arms of the trench. In the eastern arm, the upslope drystone wall was followed further, but a second stone structure, a few metres to its south, was also found. It is unclear at present what this structure is – but it was imaged clearly by the 2022 resistivity survey.

22/05/24: the process of emptying out the northern end of last year’s trench continued – with the shallower sections now bottomed. The drystone wall heading E upslope was located within the eastern arm of the trench – the first significant ‘new’ archaeology. The post-medieval deposits in the western arm of the the trench have been partially removed down to a level only just above the remnants of the downslope drystone wall in the old trench.

21/05/24: Day 2 of the dig was another hot sunny day (probably the last of those for a while!). Great progress was made on removing the backfill from the 2023 Trench and by the end of the day the 18th/19th century drain and the two stubs of the Norman drystone wall it cut were emerging well in the centre of the trench. To the west of the trench, a start was made on removing the post-medieval stony soil (which, as last year, contained fragments of human bone) and in the east some intriguing stones are starting to show close to last year’s smithing hearth.

20/05/24: the first day with the full team saw the site setup almost completed and a good start made on removing the backfill from the northern end of the 2023 Trench 1.

15/05/24: today saw the removal of the topsoil from the 2024 trench (thanks to Ken from Clive Edwards Contracts Ltd for a job neatly done!). The aim for the 2024 season is to examine a much wider area of the early features than was possible in 2023. To achieve this, the ‘L’-shaped trench will largely avoid the medieval stone walls that were studied in detail in 2023. The ‘L’-shape is intended to provide both a transect down the slope towards the stream as well as an ‘along-slope’ element to join up the areas at either end of the 2023 trench that showed such different sequences. The 2024 trench is 162m2 as opposed to 134m2 for the main trench on 2023 – of which only 21m2 reached natural, whereas we aim to reach natural over the whole area of the 2024 trench.

From the sky the overlap between the new and old trenches shows clearly. The backfill of the N end of the2023 trench shows as a much darker tone compared with undisturbed deposits around it.

15/04/24: after a busy weekend at the Cardiff University Conference on Medieval Wales, at which a summary of last year’s work was presented, focus now shifts to this season. It is getting hard(er!) to move around the office as the deliveries of consumables for the excavation arrive. The students arrive on site 5 weeks today.