Background

The Llandaff 50plus group has a acquired the long-term lease of the redundant public toilets next to the entrance of the Bishop’s Castle from Cardiff Council under a Community Asset Transfer. The extended building will become a centre for activities for older people, run by older people. The centre will perpetuate the name ‘The Pound’ for the site of the toilets was the manorial pound from at least 1717, and probably before 1607, until the 1930s. Besides the activity room, the centre will include a small heritage room manned by volunteers, to share the story of Llandaff and the Bishop’s Castle, and there will also again be an accessible toilet for both visitors and locals.

The public ‘dig’

The conversion of the toilet and its extension are one of the first development projects in the very core of ancient Llandaff in recent times, so the opportunity was taken for a community archaeological project in advance of the building works. The first part of the fieldwork was in September 2019, supported by the Lottery Heritage Fund and Cardiff YMCA (1910) Trust, involved over 200 school children gaining experience in archaeological excavation alongside a core group of adult volunteers. Over a period of two weeks they uncovered part of the late 19th century surface of the pound and its drainage system, under which a succession of deposits ranged back in age to the period of construction of the adjacent castle in the 13th century.

Finds associated with the pound included household waste including many small fragments of pottery and clay pipe, a Victorian silver sixpence, probable horse-harness fittings, horseshoes, a button and a quantity of butchery waste (during its last few decades the pound was run by Shipstones, a butchers in the High Street). Below the surface of the ‘improved’ pound of the 1890s progressively older deposits (including a pit containing a cat skeleton) represented the soil accumulation in the pound area back to medieval times. The earliest medieval deposits encountered were probably builders’ waste from the construction of the castle in the late 13th century, including river boulders, fragments of Sutton Stone (used for the dressed window and door surrounds), a spill of lime mortar, a variety of roofing materials and fragments of domestic pottery, including well-sooted cooking pots.

As the main public phase of work drew to a close, it was realised that corner of a lime-mortared cobble wall just intruded into the edge of the excavation. It seemed very likely that this was the corner of an unexpected building, lying directly below the toilets and the site of the extension. The stratigraphic context of the wall suggested that it was most likely to be medieval.

The medieval house

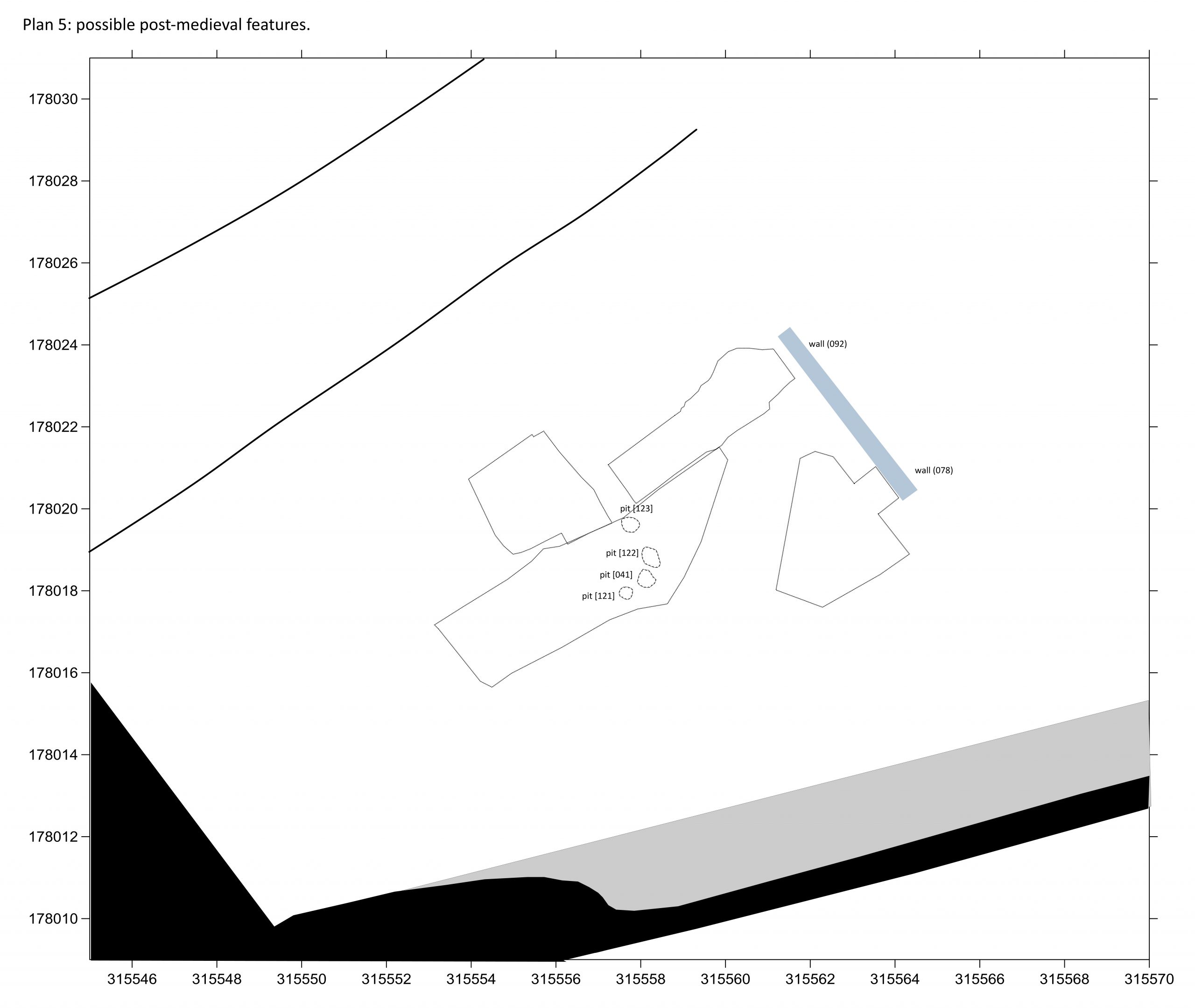

During late October and November the adult volunteers returned to the site to learn more about this medieval building before it disappeared below the new extension. It proved to represent a building of at least 8m in length and probably 6m in width, but the NE end was not found. The sump in the 1890s land-drain system abutted an offset in the lateral medieval wall and may have been positioned within a former doorway.

The building contained an elaborate fireplace with a dressed Bath stone surround in its SW end wall. The E end of the building was not located (probably lying outside the area of the Pound), but the remains of the lateral wall terminated in a aperture, probably a doorway, also with a Bath stone surround. The style of fireplace and the use of Bath stone suggests a age of fifteenth (or just possibly latest fourteenth) century.

When the house was abandoned, following the salvaging of much of the dressed Bath stone, the ground floor was largely filled with the demolition or collapse debris from the upper storey. Intercalated within the debris were layers rich in domestic waste including much pottery and bone. Small finds included brass dress pins and a fourteenth century French jeton (a coin-like token used in calculations).

The house had been constructed into a bank of material, possibly spoil from the construction of the castle, in part supported by an unmortared boulder wall. Both the dump and the wall overlay an earlier mortared stone water culvert – but this remains to be investigated more fully on another occasion.

The watching brief

The development work at The Pound has moved quickly over the last few weeks, with the inside of the block now ready to receive its new floor and the 1986 extension opened-up ready for the addition of the new meeting room.

These works have brought some exciting new discoveries: a major medieval wall under the toilets and the re-location of the boulder wall immediately behind the medieval chimney. The wall beneath the gents was as thick as any in the medieval house and probably continues the line of the front (road-side) wall of the house, but does not itself appear (so far) to form part of a structure.

The post-excavation studies

The main tasks of post-excavation have yet to be commissioned, but a lot of preparatory work has been going on. The last few collections of finds have been washed, all the finds have been sorted, with the collections from each context being counted and weighed. The quantified material is now almost ready to be sent to specialists. The major task still outstanding is the labelling of the pottery (so the specialist can mix the context assemblages to search for joining pieces). There are now almost one thousand pieces of pottery (including fragments of medieval tile) with a combined weight of nearly 9kg!

The bone collection is currently of a similar size, but this is expected to increase significantly as we process the bulk soil samples – there are indications these will contain many bones of small mammals, fish and birds.

That preliminary indication comes from the sieving of the mud washed from the pottery and bones collected from the last few contexts. Although this was only a small amount of soil, it produced teeth of voles and shrews, bones of small fish, as well as the head of a second brass pin and a further fragment of aiglet (or lace tag – a metal version of the plastic tube that protects the ends of modern shoelaces). The aiglets and dress pins are typical of the accessories required for elaborate Tudor clothes. Another rather wonderful find from the rubbish deposits in the backfill of the house is a bone tuning peg, probably from a harp. Those same deposits had, of course, previously produced the jeton.

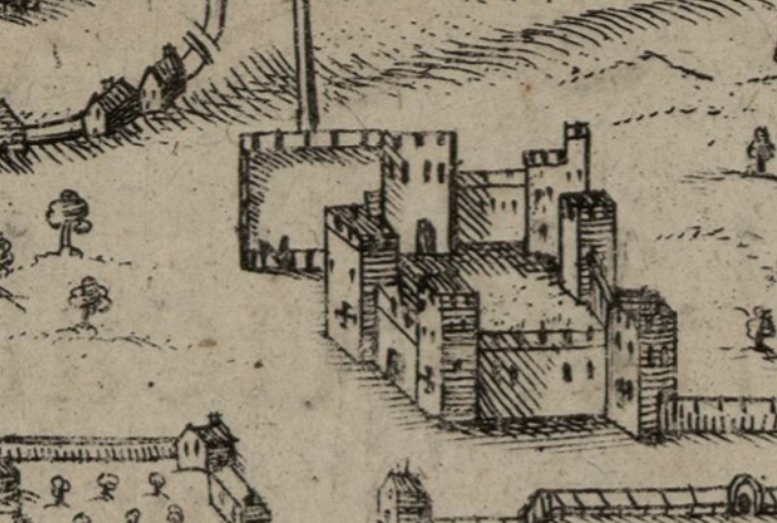

One of the challenges for the future is to try to determine whether the dress accessories and the harp peg reflect life in ‘our’ house, or whether they were amongst rubbish dumped there from elsewhere (perhaps, for instance, from the castle, which was partially refurbished at this period by the Mathews family of Radyr). It is appearing increasingly likely that the house was demolished in the late 16th century – so only shortly before John Speed drew his map, first published in 1607.